- Home

- Micky Fawcett

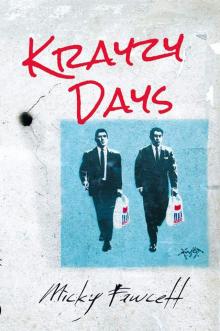

Krayzy Days Page 5

Krayzy Days Read online

Page 5

Without fail at least one docker would kick off, having to leave their name when they should have been working.

‘I ain’t signing no fucking book. I only want a fucking drink.’

It makes me laugh to think about it now – it was always the same and whoever did it would always get knocked out by the doorman. Big Tommy Brown AKA The Bear and an ex-heavyweight fighter and Billy Donovan, a local tough guy who was very handy with a cosh. Dockers were an entirely separate breed. Huge men armed with the fearsome hooks they used on the docks and they wouldn’t even see Reggie with his suit, his collar and his tie. And the sight of the doormen didn’t put them off either. Though you’d think they would back off a little bit when they saw big Pat Connolly behind the counter. Pat was the barman rather than a bouncer, but he was 28 stone – largely fat – and covered in scars. When he started swearing at you in his thick Scottish accent you knew you were dealing with a proper Glaswegian. And if you had any sense you would be properly terrified. The dockers weren’t. They always used to have a go though and they’d always be taken out. But even Pat was nervous around Ronnie Kray and no more so than the night Ronnie came in from the rain.

Ronnie didn’t have far to travel from home to his club but it was chucking it down that night and it would have been sensible to take a cab. But not Ronnie. He was just thinking to himself, Oh, this is nice. He walked all the way in his immaculate, trademark three-piece suit, the rain streaming through his hair and down his face. He must have felt as if he was in the shower. I was in the club when he made his entrance. Everyone could see the evidence of his madness as he strode damply up to the counter.

‘I’ll have a gin and bitter lemon, please,’ he said to big Pat.

The barman was terrified in the way that people often are when they see someone so completely divorced from reality. Pat could be difficult to understand when he was in full Glaswegian flow but now he carefully articulated each word as if his life depended on it. His hands shook slightly as he poured out the gin and he looked over to Ronnie who was staring straight ahead – soaked through, steaming. Pat was nervous about getting the order even slightly wrong.

‘Do you want…would you like…a bitter lemon…or a bit of lemon?’

Chapter Three

At Home with the Krays

The Krays were often embarrassingly strapped for cash. We made a lot of money when we were based out of The Double R. But none of us saved any of it. There was no cheque book or bank account for us. It was just a case of getting the money, stuffing it in your pocket and going out for the night. We all looked the part. Taking our cue from the twins, we had the suits, we had the cars and we were all very confident. It helped to convince the victims of my cons that I was successful at business. But there was no substance behind anything we did and that was sometimes humiliatingly obvious.

I saw it when we were all out in the West End one night. Back then you could order a big bottle of spirits and save what you didn’t use. You would go through half a bottle or so, the waiter came to measure how much had been consumed and when you paid he would put your name on the bottle. You’d get to finish it next time you were in. Reggie was so hard up at a nightclub owned by Danny La Rue that he discreetly poured some tonic in a bottle of gin to make it look like he hadn’t had that much. The waiters had torches so they could see the level of remaining alcohol in the dark surroundings of the club. Our man that night was startled to see what looked like tiny fish in the bottle – Reggie had poured in bitter lemon by mistake. That was how impoverished the twins were at any one time. Famous, feared, but potless.

They were just all about the publicity and being known, making sure they were seen at the right places, even if they couldn’t quite afford them. The Society, which later became Tramp, became the favoured spot for the firm. Apparently the Jermyn Street spot was frequented by Princess Margaret, which would have been more impressive were it not for the fact that it was rarer to find a London club she hadn’t visited. You imagined she’d feel at home, though. This was dining in the grand style, an experience lit by extravagant chandeliers. Far from the regular haunts. Into this elegant world came the Krays, ten-handed with Ronnie. His men always watched their boss order his favourite, double spaghetti bolognese for himself and without fail each of them asked for the same. This wasn’t because they were frightened of him – Ronnie was paying the bill. It was their work’s treat and only those who were in favour would be asked. You had to go and you had to make sure you didn’t spend more than him. A fella called Dukey Osbourne was there one night, another of the loyal mob, and raised the tone still further when wandering violinist ‘Gypsy’ Adams, who made his way from table to table, got within earshot. ‘Gyp! Gyp!’ said Dukey loudly, pausing over his spaghetti to wave a pound note he wanted to offer in return for some personal choice of tune. It’s safe to assume Princess Margaret didn’t do the same on her visit.

The West End wasn’t where we would normally start our evenings, though. It was more usually in The Double R. With the name of the Krays attached, it was the place to be. The legendary Jack Spot once came in the club with a friend. Johnny Carter was a fellow gangster whose leg, in an incident more reminiscent of Monty Python than criminal activity, South Londoner Frankie Fraser was said to have tried to saw off. I have no idea if it was true, though I did know that Carter was definitely a tough guy and he came from a mob based over the Elephant & Castle. As a younger man coming up myself, I paid quite a bit of attention to these myths and legends. I could see how handy it was to have a good story.

The regular crowd in The Double R were a tight circle of friends. We all started off just as the Krays themselves were beginning to find success. We were the nucleus of the club itself – Georgie ‘Ossie’ Osbourne, Dukey Osbourne, Johnny Squib, Dickie Moughton, Billy Donovan, big Pat Connolly, Tommy Brown and Dicky Morgan. Pat was intelligent and a bit warm, shrewd. The rest of them were loyal but over time the group fell apart as the twins became more erratic and it had disastrous consequences for Ossie.

The twins introduced him to La Monde, a smart drinking club in the World’s End area of the King’s Road in Chelsea. Ossie became close to the owner, Jamette – a very evil woman – and eventually shared her flat above the club. Jamette had emboldened the twins after telling Ronnie that the then commissioner of the Met, Sir Joseph Simpson, was a closet masochist who she would regularly whip and abuse to order and she assured them she could handle him. This same woman was the one who, when Reggie chinned Bimbo Smith knocking his false teeth out, stamped on them, and on her daughter’s 16th birthday asked Ronnie to deflower her. Ronnie duly obliged.

One evening Ossie didn’t feel like coming down to play host to Ronnie and his party and Ronnie went berserk. He ripped the club apart, tearing the decor off the walls and trashing the furniture. Ossie never seemed to get over the shock of Ronnie’s reaction and died from a heart attack not long after.

But the notoriety of the Krays’ name ensured that despite their behaviour, more people joined the group – what became the firm – and eventually it got too unwieldy. It was the sheer number of hangers-on and celebrity spotters that would prove to be the undoing for the Krays. It was ironic in a way – we were much tighter in the early days and we were at our best long before anyone had thought of calling the Krays a ‘firm’.

In those early years, there were a few among us who liked to go out during the day and a popular destination for them was The Spieler, a gambling house in Wellington Way, almost opposite The Double R. It wasn’t for me. I never used to gamble. Didn’t know how, didn’t want to know. I’d had a go once when I was 15 and I lost all my factory wages. But The Spieler was popular enough; it was next door to a police yard and it eventually got raided but it was somewhere you could go for a cup of tea and where you might arrange to see people over The Double R later in the evening.

I preferred The Double R itself and when that closed we headed to the West End for a big night out. Everything revolved around drinking bac

k then. We socialised together but that’s also how most of our business was done. I didn’t know anyone who didn’t drink – there would have been something suspicious about someone who didn’t. Everything was done in a bit of a soft haze. And I knew all the best clubs in the ’60s. I loved them and in the West End they were far less male dominated than The Double R. The nightclub hostesses formed a major part of the attraction of the times and, besides, it was different at The Double R once the Colonel had come home. The Krays’ place wasn’t somewhere you’d go out with a girlfriend or with the wife. You had to be on your guard and know who Ronnie Kray was speaking to and who was out of bounds. There was one bloke who we were told to ignore one night – a reporter for The Sunday People called Tom Bryant. His crime was to file a nasty piece about a friend of Ronnie’s called Frank Mitchell. He called him ‘the mad axeman’.

‘We’re having nothing to do with him,’ said Ronnie. ‘He’s been coming in here and we’ve been right friendly with him and now he’s wrote that piece in the paper.’

I don’t even recall if I saw the offending article but I wouldn’t forget being told to blank him. Mitchell had escaped from Broadmoor and found a house with an old couple. He told them to behave themselves and picked up an axe by way of suggesting what might happen if they didn’t. Bryant gave him the nickname, which stayed with him for the rest of his life. Ronnie ignoring Bryant was all part of the big boss image he liked to project.

I remember where I first ran into Ronnie. Behind Mile End Station there used to be a billiard hall. There was a cinders pitch, an area of paving between the two buildings, and I was heading across the cinders to the hall to speak to Reggie. I saw him – or I thought I saw him – near the hall.

‘Reg!’ I called out. He turned around slowly and replied with the nasal sneer that was often in his voice.

‘I think you want my brother.’ There was something unnerving about his measured, deliberate delivery and the way he looked at me. He’d just come home at that point. One trouser leg was shorter than the other and you could see a hole in his sock. He wasn’t alone, though I don’t remember who it was who accompanied him. I do know that he went away again not long after that.

Eventually Ronnie returned for good and settled back into life in the area and I inevitably got to know him as a result of being good friends with Reggie. The twins were often as not both at their family home, 178 Vallance Road, off Whitechapel Road and between Brick Lane and The Double R. It was a small house and they used the front rooms both upstairs and downstairs for receiving visitors. There was a short hallway from the downstairs front room to a small kitchen with a table, which made it the dining room as well. Next to that was a scullery space of the type where a family might drag in the tin bath. Straight people were never invited, though even those who had just got out of prison and had come to pay their respects to the twins were received with utter contempt. The Krays had no time for them, dismissing them as ‘jailbirds’. They had little time for anyone, to be honest.

New faces were given an initiation of sorts by the caged mynah bird lurking in a corner of the kitchen. ‘What’s your name!’ it said, sounding like Ronnie himself, rather whiny and nasal. Reflecting the main concern of the household it could also say, ‘Some money! Get some money!’ as well as ‘Mum! Maaahhhhm!’ As an encore it could do old Charlie senior’s hacking cough and a passable version of the trains rumbling by on the viaduct up the road.

Guests in the kitchen were perched on a chair with their back to the bird and it sometimes took advantage of those who hadn’t noticed it. But the twins hadn’t bought the bird deliberately to give people a shock. Most visitors were nervous enough just being in the presence of the Krays and would leap up in terror when it chipped in loudly with its choice phrases – ‘What’s your name?’ causing particular panic.

I spent many hours in that house and got to observe the twins at close quarters. They were never really off duty but when they were relaxed, Reggie – the more stable of the two, at least in those days – demonstrated no sense of humour whatsoever. Ronnie never stopped laughing. Even when a mate bought over a copy of Private Eye that lampooned the pair of them. I’d been reading the satirical magazine since it came out and was a fan of Richard Ingrams but neither of the twins had the faintest idea what The Eye was about. Among its other achievements, it was the first publication to feature the Krays. The piece that Ronnie saw was written very much in the style of the twins and made merciless fun of them. Ronnie howled with laughter and it kept him amused all day. All his visitors had to read it and he long referred to himself as a ‘well-known thug and poof’ in general company. Reggie forced a smile but you could tell he just didn’t get it. Private Eye’s interest in the twins later helped to popularise the idea that they were somehow cool and part of the Swinging Sixties, but that was very wide of the mark. They were always apart.

The twins themselves were not into popular culture, even as they were becoming part of it. It may well have been the piece in The Eye that caused the Oxford Student Union to have a close escape when they invited the twins to take part in a debate, the subject, ‘Is the law an ass?’. The twins were terrified at the thought of it and the invite was kept a closely guarded secret amongst a select few. I shudder to think of their reaction when some young intellectual would have undoubtedly had them tongue tied and floundering. I was unusual in their crowd for liking all sorts of comedy, not just The Eye, and I loved French gangster movies. Still do. Classe tous Risques (Consider All Risks) is a favourite; a 1960 film with Lino Ventura and Jean-Paul Belmondo. Another Ventura classic was The Second Breath – Le Deuxième Souffle. It was more recently remade, but it wasn’t as good as the black-and-white original. Sometimes you shouldn’t go back. The twins didn’t go to the pictures at all but I think Ronnie would have liked Repo Man, the Alex Cox film from the 1980s. Harry Dean Stanton is in his car when he looks around and says, ‘Ordinary people. I fucking hate them!’ It’s still one of my favourite lines in any movie.

Ronnie said something similar about the straight world when were sitting in a car outside a pub in Bow; he was looking to stick it on someone or other and he was feeling particularly full of bitter hatred. He was rather less elegant in his description than Stanton as he gazed at his fellow drinkers.

‘Look at them. Fucking hate them,’ he said. ‘I’d like to hold them down and let a black man fuck them.’

Both brothers really did despise almost everyone – straight and criminal. It was just the world of the middle and upper classes that both brothers respected. They always hoped they would be able to join them some day. But that wasn’t the same as liking. That was wanting something they’d never had. They were generally just very antisocial and dismissive of anyone they couldn’t use. The best you could hope for was to be accepted – and that applied to me as much as anyone else. It was all just business.

They dressed to reflect their aspirations and to show how far they’d come. When they were young the family business had been clothes buying, but it was all second-hand. As kids they would go cold calling with a bag to ask for unwanted old clothes, though they would take any old gold and more or less any old anything. Once home, they cleaned and pressed the clothes and then I guess they sold them on. By the time I knew them they could splash out on anything they wanted and their taste was another way to tell them apart. Ronnie wore a Savile Row suit and crocodile shoes whereas Reggie was strictly East End, his suit from Woods the Tailor on Kingsland Road. If Reggie was an East End boy then Ronnie was a West End girl.

It was usually open house at Vallance Road, as long as you were respectful to everyone and everything there – that was what it was all about. You had to match their style too. They were surprisingly prim and they’d never mention bodily functions in conversation. On the surface their place was a model of suburban respectability, tidy and a bit severe. But only in appearance. The twins’ mother, Violet, often written about as the Queen Mum of the East End, set the tone. I would often meet wit

h the twins in Pellicci’s, the cafe at the top of their road – it’s still there. One day we had a cup of tea before heading back to Vallance Road where she opened the door.

‘Did you see that fella, Reg?’ she said. ‘I sent him down the cafe to see ya.’

‘Yeah,’ said Charlie. ‘Reggie nutted him.’

‘I thought he would,’ she said.

Reggie himself added, ‘He was a fucking nuisance.’

Family dinners were no safer. Not even the day Ronnie, kitted out with pressed trousers and braces, was enjoying a big, steaming bowl of chunky stew. An English bull terrier dozed by his feet. Dukey Osbourne was also there. I could hear old Charlie’s tread in the corridor outside and Ronnie squawked like his mynah bird, ‘Maaahmm! Maaahhhhm!’ He hated his father. ‘It’s the old bastard!’

Like his sons, old Charlie always wore a nice suit – particularly when he was out drinking, which was quite a lot of the time. Setting great store by his ability to clean and press clothes, he claimed he could get all the blood out of his sons’ outfits after they had been fighting. He staggered through the door, adjusting his tie and his cuffs. Ronnie continued with his baiting.

‘He’s here, Mum! Rotten, drunken old cunt!’ Violet was working in the kitchen and although she must have heard the complaints, she didn’t respond.

Charlie sneered. ‘What I’ve heard about you today, son. Well, I never. Can’t believe it,’ he said. ‘You’re gone! You’re gone!’

Ronnie’s eyes had become fixed, staring. His hands gripped his knife and fork very hard. Without turning, he slid his eyes around to gaze at his father as his whole head shook with rage.

Krayzy Days

Krayzy Days